Horses rid themselves of discomfort in many ways. Comfort-seeking behaviors in horses serve a variety of functions, including physical relief, stress reduction, and psychological satisfaction. They are one of the many maintenace activities horses engange in throughout the day.

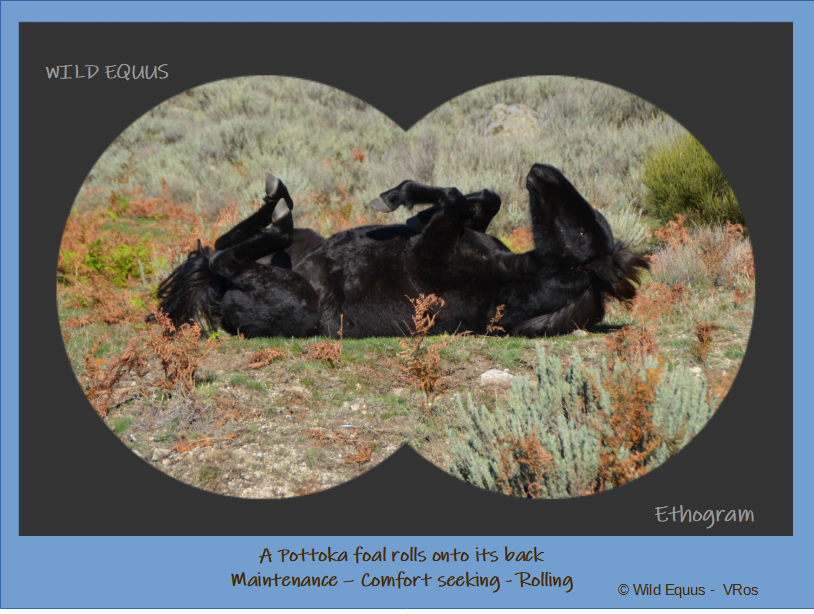

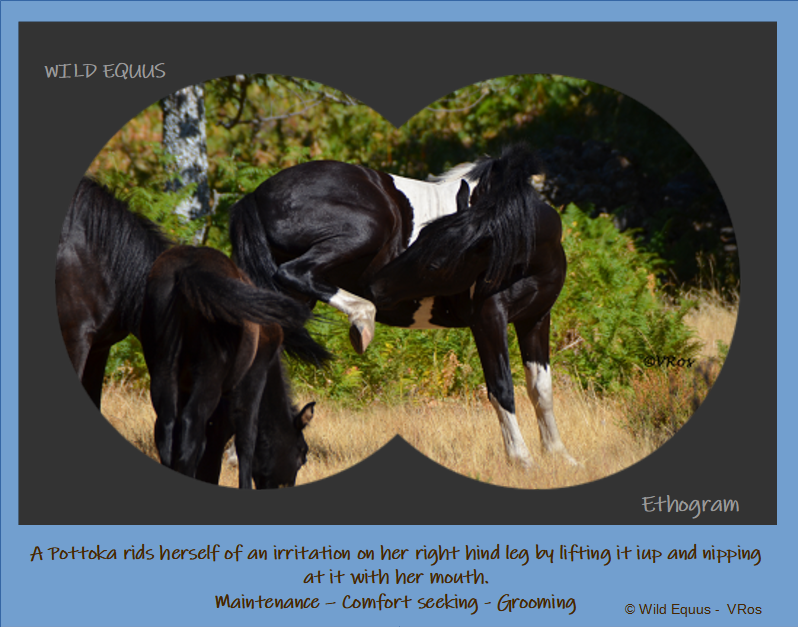

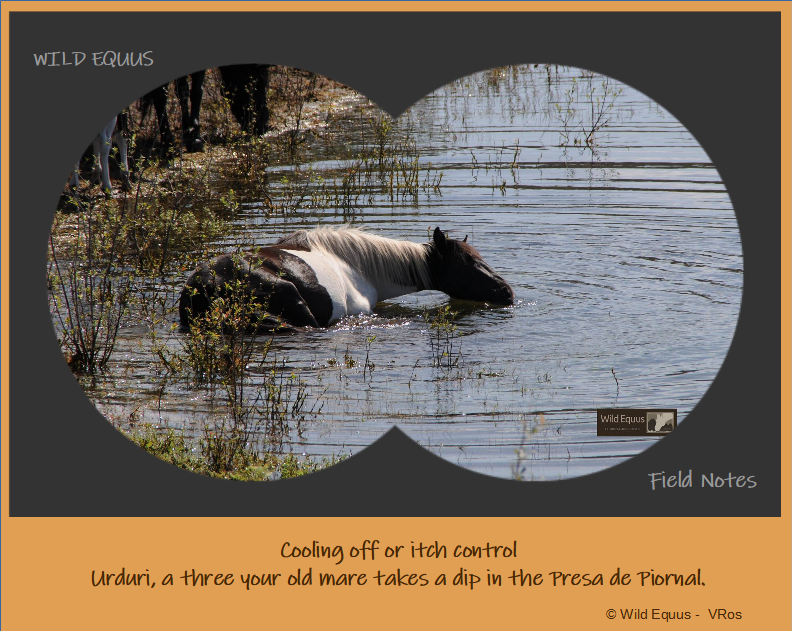

Physical functions of comfort-seeking behaviors include relieving physical discomfort or pain. For example, horses may roll to alleviate itching caused by insect bites, or they may stretch to release muscle tension or soreness. Similarly, self-grooming, such as biting or scratching the skin, can help remove parasites and dirt from their coats, which can reduce skin irritation

Comfort-seeking behaviors serve behavioral functions such as reducing stress and anxiety in horses. These behaviors are often displayed in response to stressful situations such as separation from the herd, moving to a new location, or exposure to loud or frightening stimuli. Rolling, for instance, has been demonstrated to decrease heart rate and cortisol levels, which are reliable markers of stress in horses.

There are also psychological functions such as providing oneself a sense of comfort and satisfaction from actively reducing discomfort.

Grooming (g)

In general, grooming in horses encompasses all types of skin, coat, and bodily care. Self-grooming involves behaviors that focus on taking care of one’s own body, while allogrooming refers to care directed towards another individual. When two or more horses engage in reciprocal grooming behavior directed at each other, they are involved in mutual grooming.

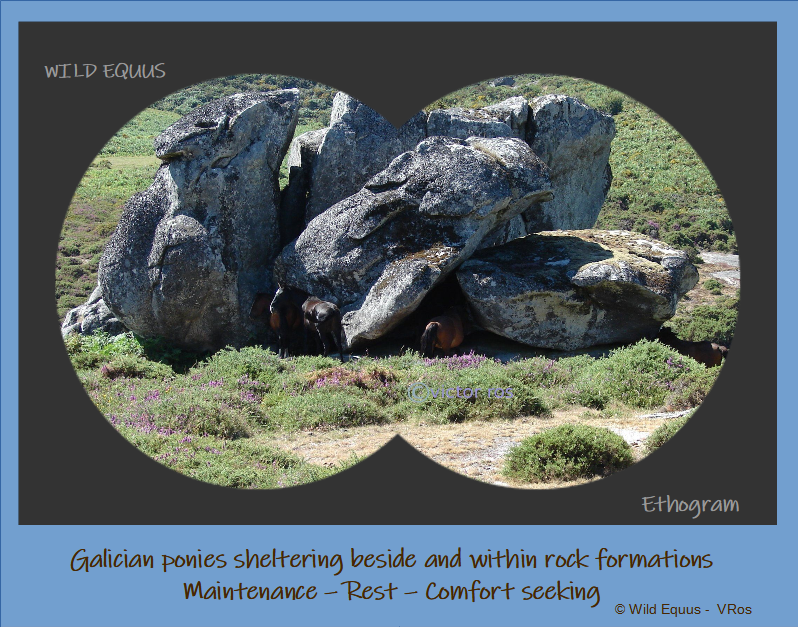

Horses have a large repertoire of behaviors to rid themselves of discomforts brought about by an itchy pelage, biting insects, or inclement weather.

Horses have various ways to remove flying insects from their bodies. Twitching, which is a localized contraction of cutaneous muscle, is a common method. This cutaneous Trunci muscle reflex helps to get rid of insects. Additionally, shaking of the head or body is also a common response to winged irritants. Another effective method of removing these pesky ectoparasites is striking one part of the body against another. Tail swishing is the most effective strike, which horses often use to get rid of flying insects.

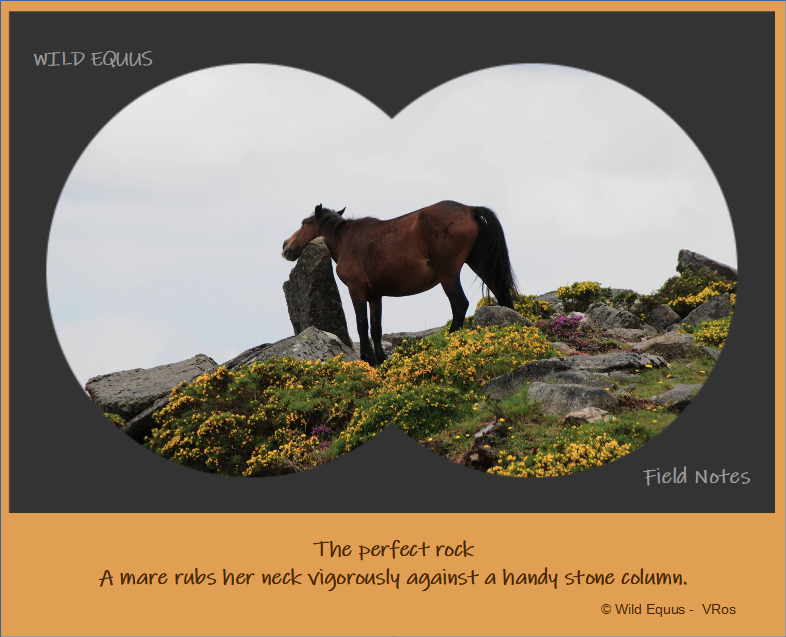

Horses have additional ways of self-grooming, such as stomping a leg on the ground or rubbing against features in their environment. They may also scratch and nibble at their own bodies using their teeth. Or rub against an object, including another horse. Rolling is also considered a form of self-grooming for horses, with the exception of ritualized rolling between stallions.

Allogrooming (alg)

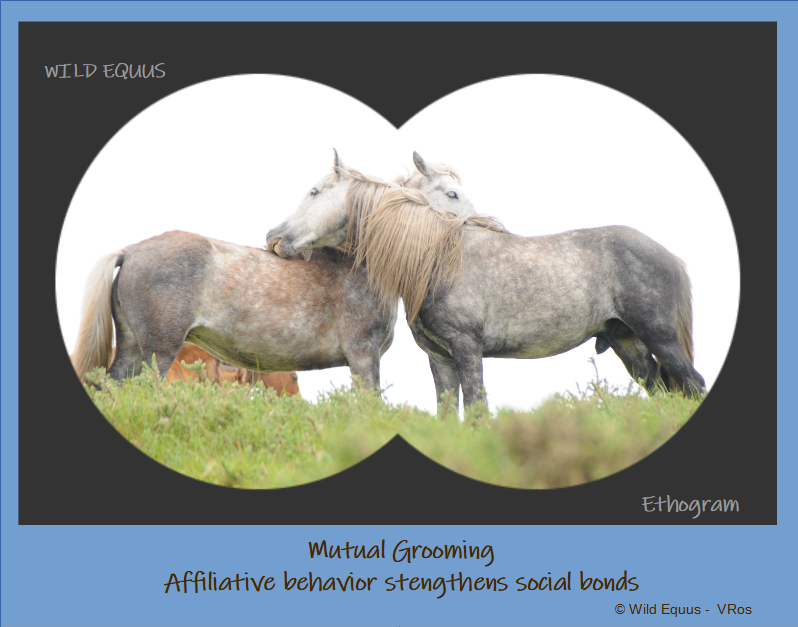

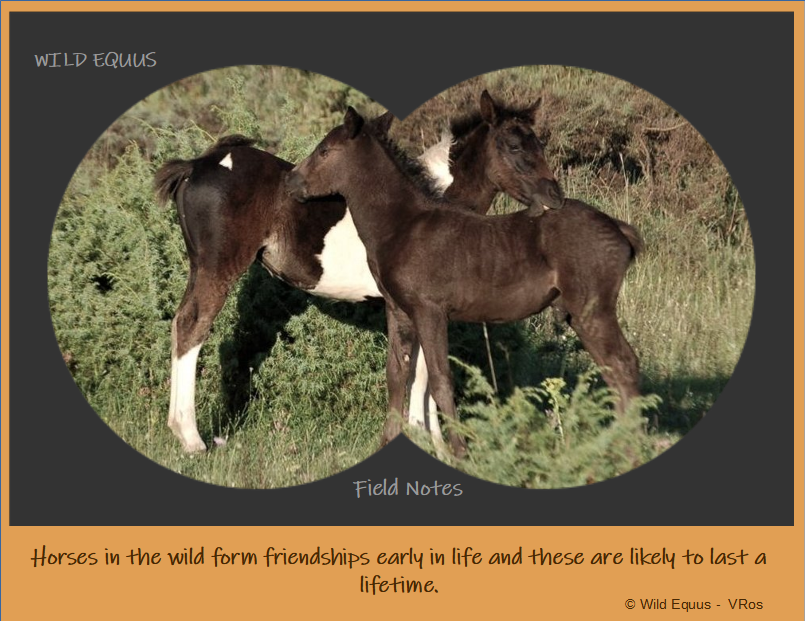

Allogrooming, also known as social grooming, is when one horse grooms another. This behavior can be classified into two types: uni-directional grooming and mutual grooming. Uni-directional grooming occurs when one horse grooms another without being groomed in return, while mutual grooming involves two or more horses grooming each other at the same time. (McDonnell, 2003).

Social grooming serves a dual purpose, as it not only relieves horses of discomfort caused by itchy skin or biting insects, but it also reduces the heart rate and cortisol levels of the individuals when directed at certain locations (Feh & Mazieres, 1993; Haverbeke et al., 2002; Dierendonck & Goodwin, 1992) and helps to reinforce social bonds. (Dugatkin, 1997)

When two horses engage in mutual grooming, it usually begins when one or both horses approach each other head-on with ears forward and mouth slightly open, exposing their lower teeth. (Feist & McCullough, 1976; Tyler, 1972)

During a typical mutual grooming session, two standing horses face each other and nibble at each other’s necks, manes, forelegs, and withers. (Tyler, 1972) They may also stand antiparallel, with their heads positioned near each other’s shoulders for the grooming session.

According to Feist & McCullough (1976), mutual grooming among horses only occurs among members of the same group and can involve any combination of group members. Both, with the feral creoles of Venezuela and the free-roaming ponies of Galicia, we observed mutual grooming between members of two different bands. This is likely due to a more compact spatial distribution, and similar activity patterns. Bands were found resting in close proximity to one another in both locations, and social interactions were not uncommon between members of neighboring bands.

In contrast to the competition-reconciliation model, where the frequency of grooming received is related to an individual’s status, this does not seem to be the case for horses.