Hemos recuperado este articulo escrito originalmente para la revista Horse Evolution en septiembre 2016.

¿Cuánto sabemos y cómo se puede mejorar su bienestar?

“La única constante en la vida, es el cambio”. Nuestra forma de ver y entender a los caballos, también cambia.

Nuestra milenaria relación con los caballos ha quedado plasmada en pinturas rupestres que datan en más de 15.000 años . Les cazábamos como fuente de alimento y para obtener cuero. Con toda probabilidad, el éxito en la caza, dependía en parte de nuestros conocimientos sobre el comportamiento y los hábitos de las presas.

Con el paso del tiempo conseguimos domesticar a los caballos hace unos 5.000-6.000 años. Les sacamos de los entornos en los que habían evolucionado, y les proporcionamos unas condiciones ambientales que eran más provechosas para el ser humano. Su domesticación supuso un gran cambio en nuestra forma de relacionarnos con ellos, pues los teníamos “más a mano”. Este hecho, facilitó una diversificación de las formas en las que podíamos sacarle a este animal más provecho; tracción, transporte, deporte y ocio.

Después del largo recorrido juntos, sería lógico pensar que sobre caballos sabemos mucho. De hecho, es así. Sabemos muchísimo, al menos lo suficiente para ofrecerles una vida más saludable sea cual sea su rol doméstico, ya que además de los avances científicos, nos avalan miles de años de experiencia.

Existen unos 60 millones de caballos en el mundo. Como el hombre y el perro, supone una de las especies más cosmopolita, pues se puede encontrar en casi todo los países del mundo. Desafortunadamente, la mayoría sigue viviendo en condiciones “infraequinas”. Condiciones a las que no se pueden adaptar bien, a pesar de los miles de años que han pasado desde su domesticación. En parte, esto se debe a la ignorancia, por una falta de conocimientos generales en ciertos sectores de la población. En ocasiones, también los conocimientos que tenemos chocan frontalmente con nuestras creencias o tradiciones culturales. En este caso, dejamos de considerar y aceptar nuevas formas, aunque los conocimientos estén disponibles.

A lo largo de nuestra trayectoria con los caballos, nos acompañan dos corrientes de pensamiento muy opuestas. La primera, es considerar a los animales como meros autómatas, máquinas carentes de conciencia y sentimiento. Esta creencia ha legitimado pésimas condiciones de vida, y gran parte del maltrato que siguen sufriendo hoy los caballos. La otra corriente es el antropomorfismo; atribuirles características exclusivamente humanas a los animales o a los objetos. El antropomorfismo, hasta hace relativamente poco, era un tema tabú para la mayoría de científicos, ya que suele ser perjudicial considerar que las necesidades de los caballos, motivos, y conductas sean iguales a los nuestros. Y a su vez, porque negar que los tengan, aunque en diferente grado que nosotros, les perjudica aun más.

Afortunadamente, la progresiva acumulación de avances científicos sobre caballos y otros animales, nos ha brindado la oportunidad de comprender como nunca sus hábitos y conductas naturales. Estos avances ayudan a cuestionar muchos dogmas, tanto antiguos como nuevos, que asolan el mundo del caballo en el ámbito humano.

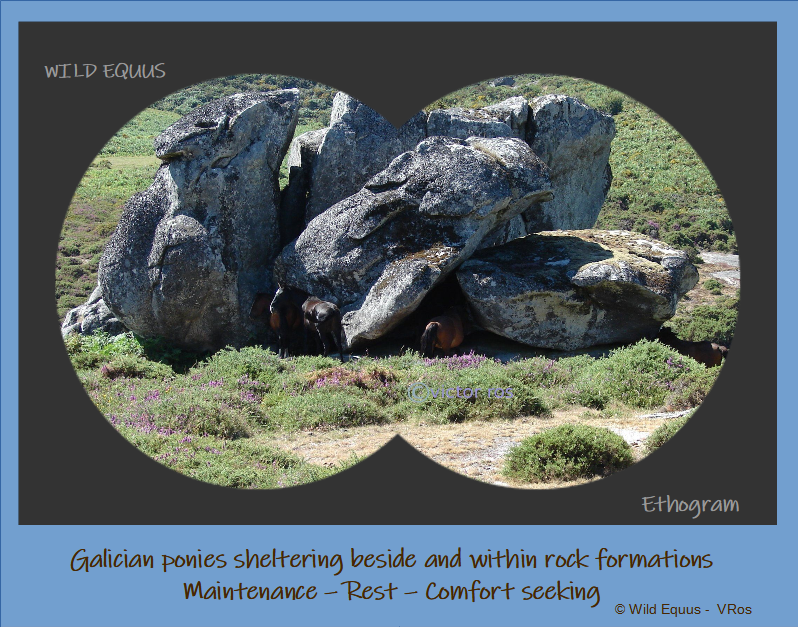

Debemos recordar que el comportamiento es la primera línea de defensa de los animales, son sus herramientas biológicas para poder interactuar con un entorno en constante cambio. La etología, estudia estas herramientas en entornos naturales (o simulaciones de ella). Se observan, describen, miden e interpretan conductas para entender y explicar patrones, procesos, y las estructuras mediante las cuales los organismos se adaptan a su entorno; su función biológica.

Uno de los principios fundamentales de la etología, es que los comportamientos, igual que cualquier otra característica de los seres vivos, son fruto de la evolución y por tanto modificados por la selección natural; los rasgos que confieren una ventaja reproductiva a un individuo sobre el resto de una población, serán seleccionados para pasar su genética a futuras poblaciones.

Cuando estudiamos las conductas, intentamos averiguar sus causas. Podemos diferenciar dos tipos de causas; las proximales y las distales. Básicamente, las proximales explican cómo funciona un comportamiento a través de sus causas fisiológicas o ambientales. Sin embargo, las distales se centran en el “por qué” de los comportamientos a través de las fuerzas evolutivas que actúan sobre ellos. De hecho, las causas últimas predisponen a los organismos para reaccionar ante las causas próximas.

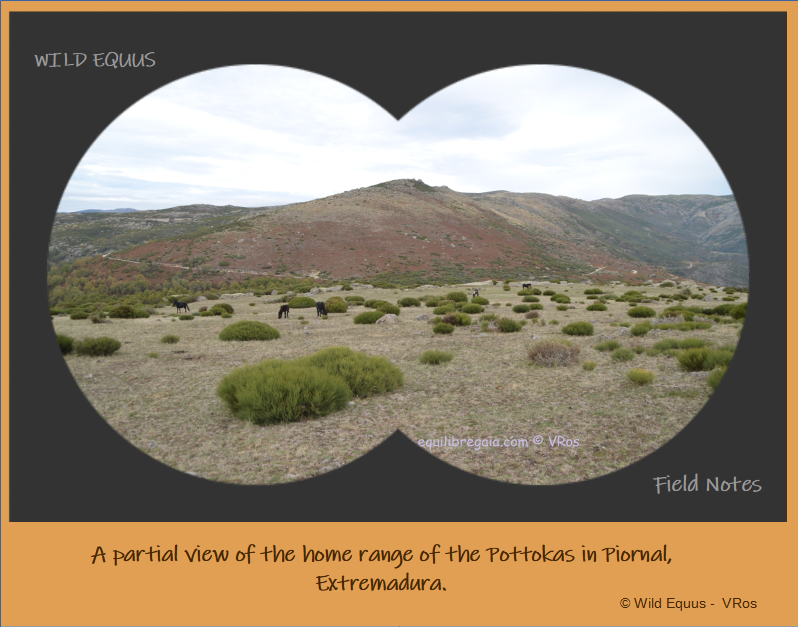

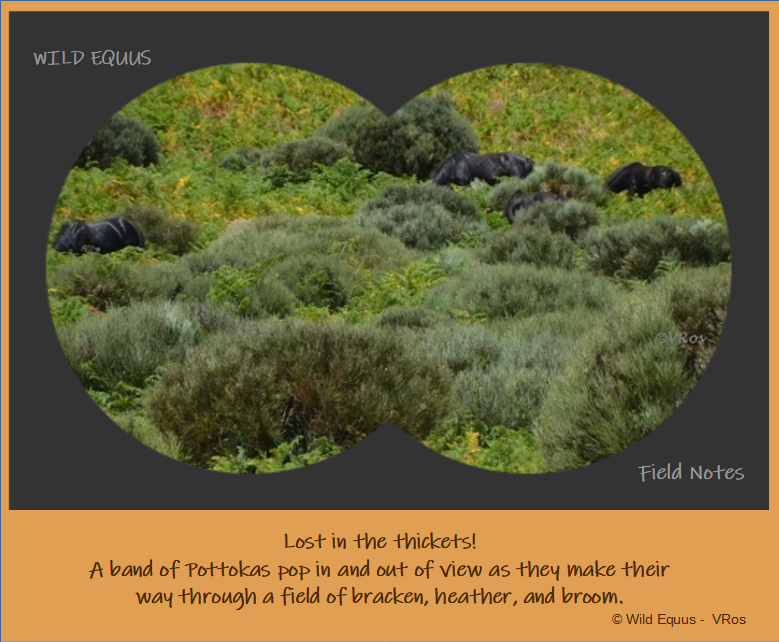

Con esto en mente, es imprescindible entender cómo los caballos se comportan viviendo libres y sin la intervención del hombre. Sus conductas en un entorno natural nos proporcionan una vista holística de cómo solucionan su día a día en un entorno para el cual están mejor adaptados. Sin embargo, la gran mayoría de caballos no viven en su entorno natural, ya que los hemos incorporado al nuestro. Un mundo muy diferente, uno “usual” para caballos domésticos, pero lejos de ser natural.

Durante siglos hemos estudiado a los caballos en condiciones “usuales”, culpándoles a veces por comportamientos indeseados, cuando sólo reflejaban su incapacidad de adaptación a un medio hostil. Las estereotipias son un claro ejemplo de una vida ‘infraequina’.

La elevada tasa de agresión que observamos en entornos sociales domésticos, no tiene nada que ver con lo que se observa cuando los caballos viven como caballos. Estudios comparativos nos indican que los caballos domésticos tienen tasas más altas de agresión que los que viven libremente; de 47 agresiones por hora entre caballos alimentados con cubos de concentrados, la tasa de agresiones bajó a 13, cuando esos mismos caballos fueron soltados en un prado. Aunque la bajada en la tasa de agresión es importante entre estas dos situaciones, en comparación con las 1,9 y 1,2 agresiones/hora observadas en caballos ferales, sigue siendo altísima. Durante años, la culpa de muchos de sus hábitos indeseados se les atribuía a los animales en sí.

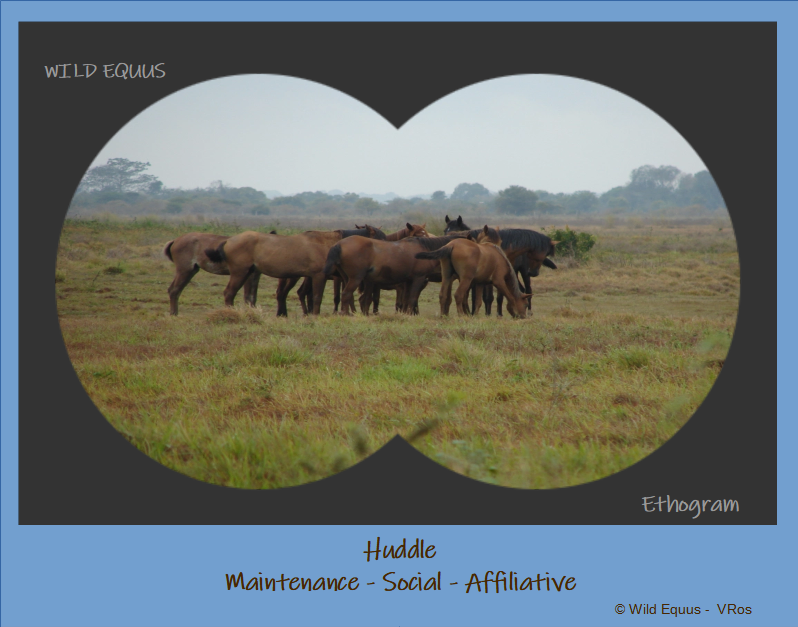

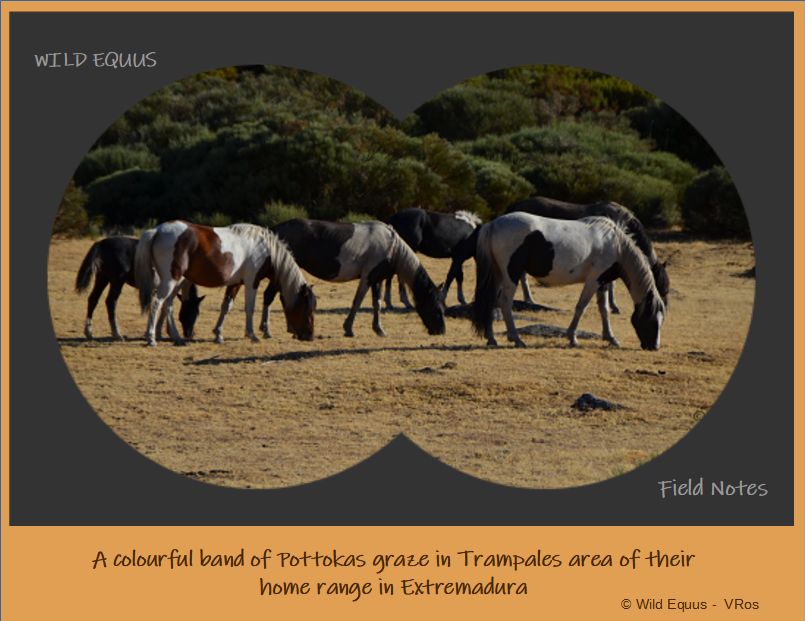

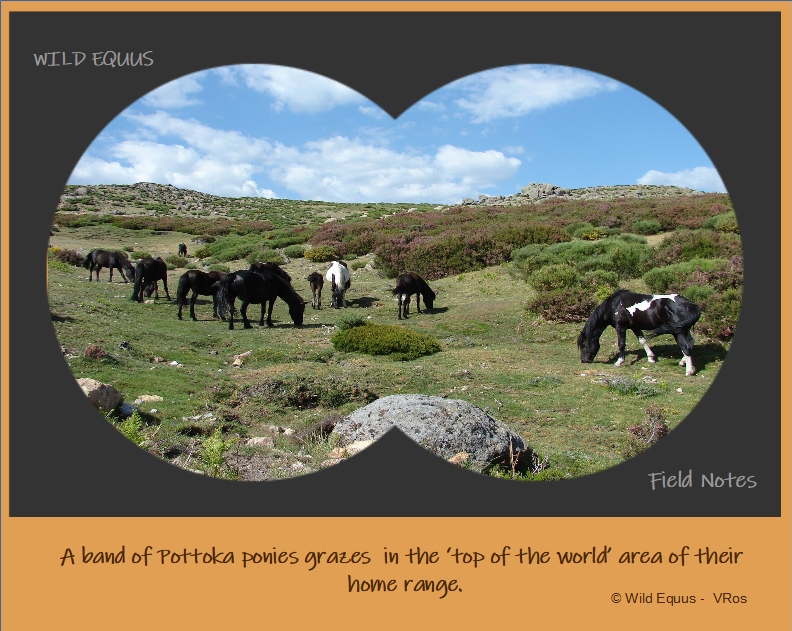

Ahora, esto ha cambiado. La mayoría de personas involucradas con los caballos, entienden que el bienestar de éste, se promueve cuando el animal es capaz de realizar las actividades que más se parezcan al repertorio conductual de sus conespecíficos viviendo en libertad, es decir, su comportamiento natural. Una comprensión de sus patrones conductuales, propios para cada especie, nos facilita mucha información acerca de sus requerimientos básicos, preferencias y aversiones. Gracias a la etología y otras disciplinas, hemos acumulado un sinfín de estudios sobre caballos que nos ayudan a entender sus pautas de comportamiento, sus ricas vidas sociales, y su nicho ecológico.

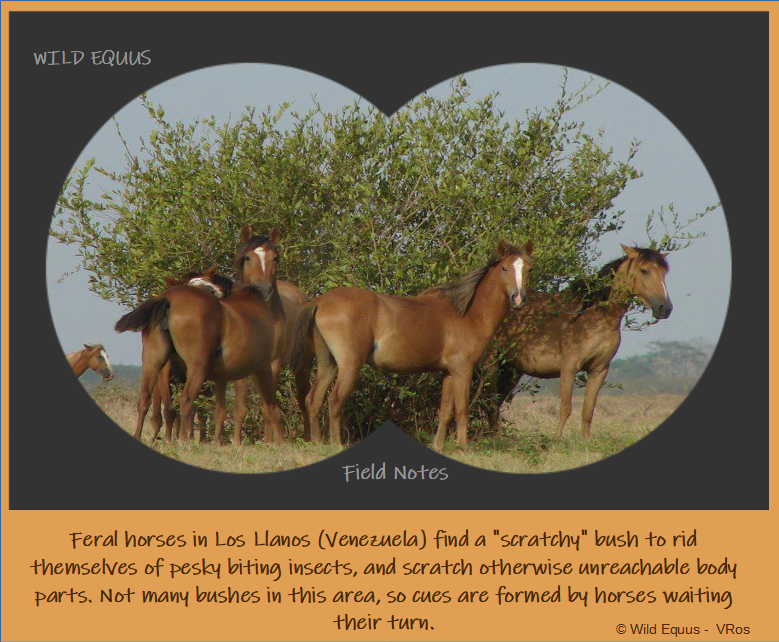

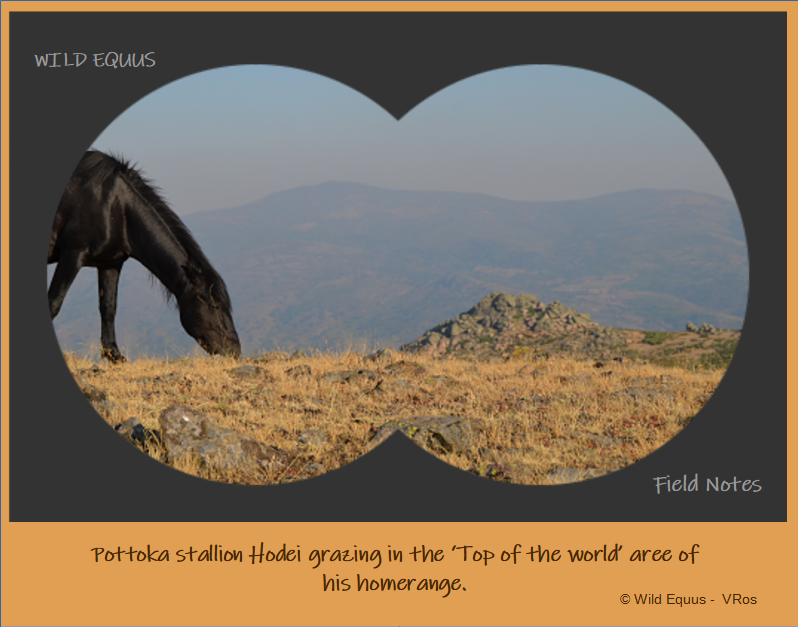

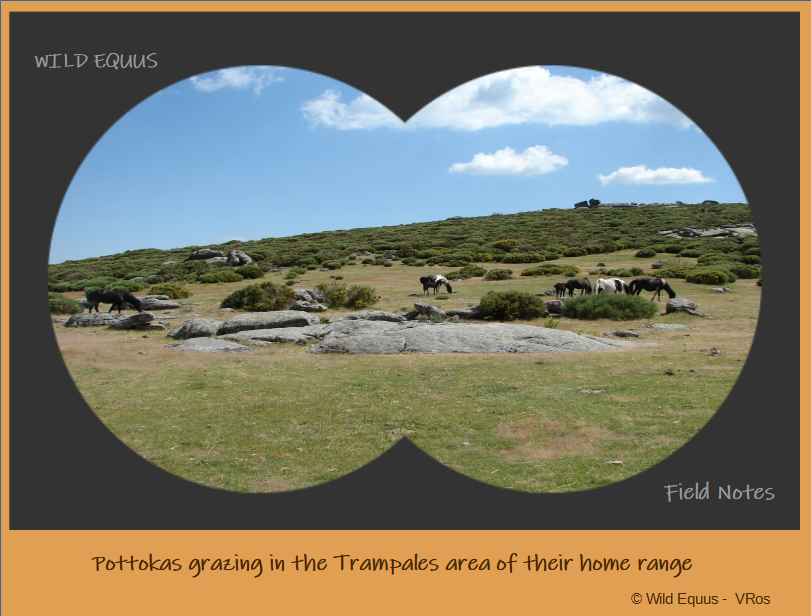

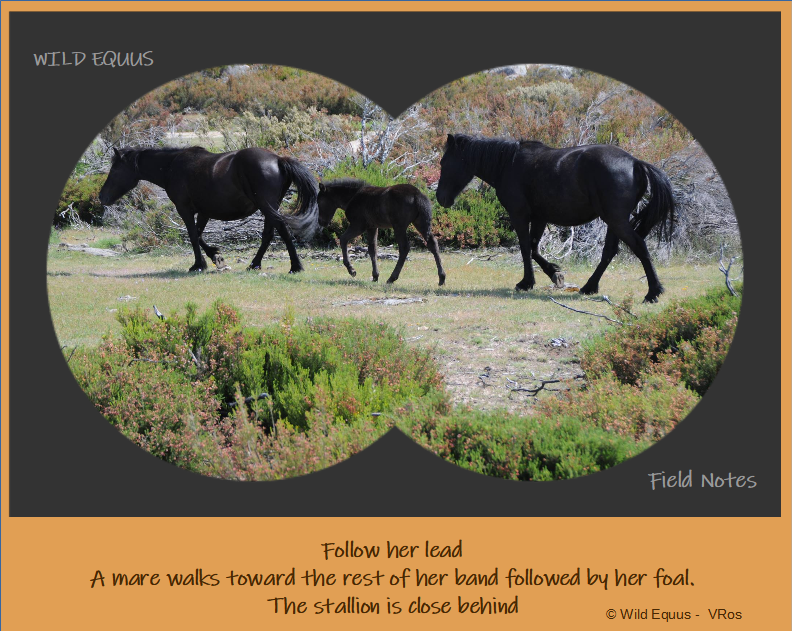

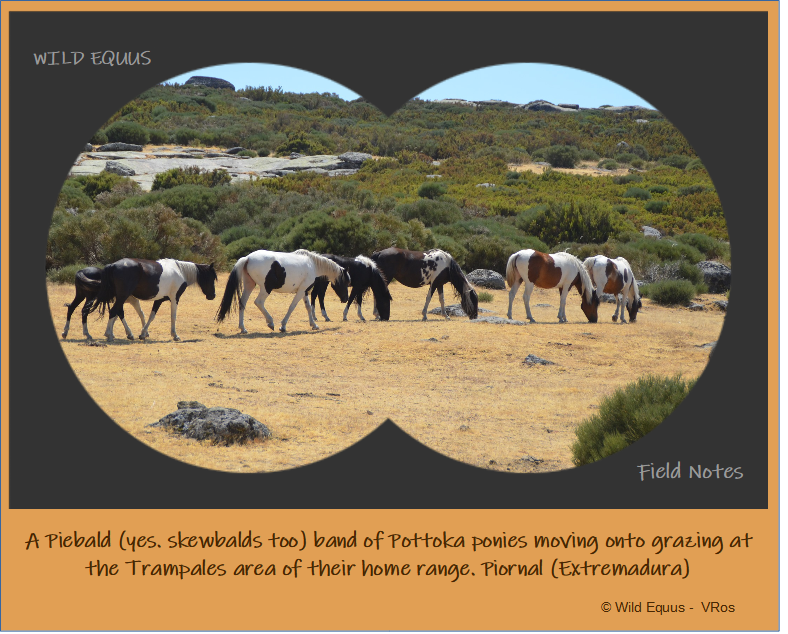

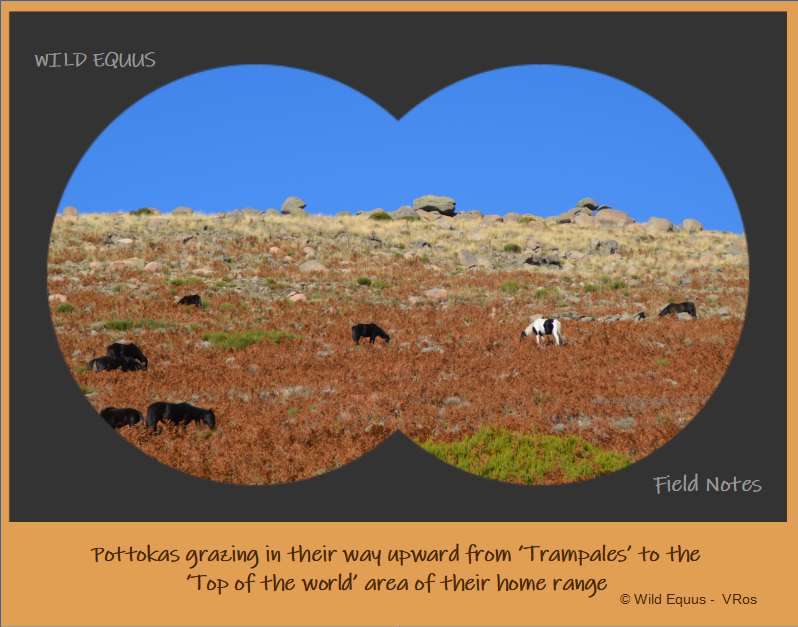

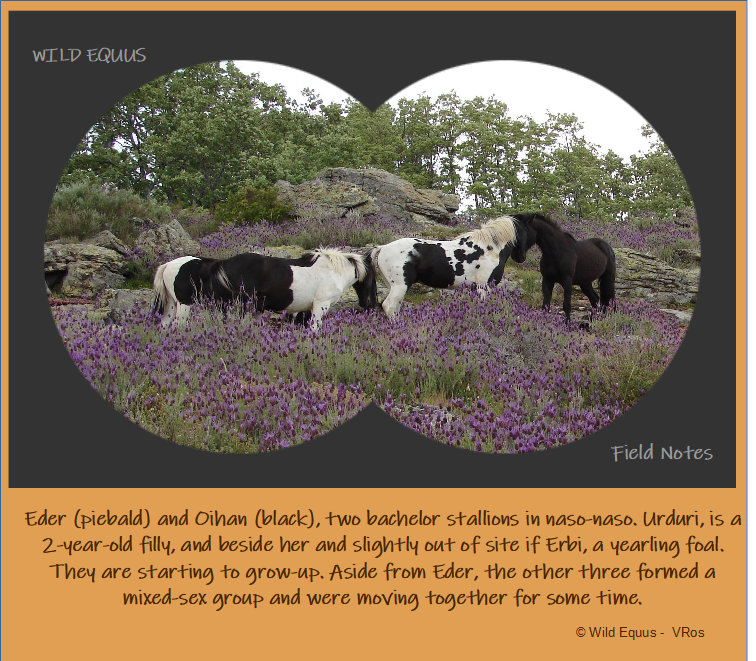

Con la etología aplicada a caballos domésticos, también entendemos mejor como los caballos, sacados de su estado natural, reaccionan y hacen frente a los desafíos en su entorno y manejo humano. La suma de estos estudios nos indica que la domesticación puede haber alterado muchas características físicas a lo largo de los años, pero las conductas típicas de la especie, han cambiado poco. De hecho, en casi todas las poblaciones de caballos ferales estudiadas, surge una lógica conductual aplastante, su ‘ethos’, esculpido por millones de años de fuerza evolutiva. En cualquier lugar que los caballos se hayan soltado o escapado, por omisión, se han observado características muy similares, pero no necesariamente iguales. Son herbívoros que viven en bandas sociales, y juntos pasan la mayor parte de su día (entre 15 y 18 horas) pastando variedad de forrajes.

No es sorprendente que negándoles la oportunidad de expresar estas conductas perjudiquemos su bienestar, aprendizaje, manejo, y rendimiento. En las próximas entregas, nos adentraremos en el fascinante mundo natural de los caballos, y como los conocimientos etológicos nos ayudan mejorar la calidad de vida de nuestros caballos.